My Newspaper Days

Flog my dusty Super Beetle to the Register parking lot,

stay in my car to eat a ham sandwich, dry shave my stubble,

knot my grease-specked tie, flatten my flaring brown hair.

Grab the day’s first Diet Pepsi, stride into the newsroom

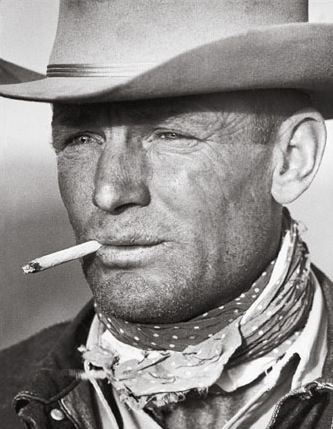

with its clusters of metal desks, cigarette and cigar puffers

exiled to a cloudy corner under the relentless wall clock,

lift my cold can to greet others who didn’t sleep in

after covering a meeting that dragged into the wee hours.

Sigh into a swivel chair in front of my typewriter if it’s ’80,

my computer if its ’83, read a note left by my editor,

sometimes clipped to a press release or a letter about a girl

selling her pictures to pay for her brother’s kidney transplant.

When you’re a general assignment reporter, you know

your words will get good play envied by those whose stories

about school boards and city councils are buried in back.

You better be clever, swift, empathetic, careful not to burn out

or make an embarrassing blunder requiring retraction.

Missed deadlines will get you demoted to a small-town beat

that forces you to keep a poker face while windbags

grouse about traffic flow, drainage ditches, trash pickup.

With a narrow reporter’s notebook tucked into my pocket,

sipping a fresh Diet Pepsi, bobbing my head to radio rock,

I maneuver on bald tires through Orange County, a region

of beaches, mountains, megachurches, oil rigs, Disneyland.

Cover a hillside brushfire, ride in a helicopter with a cop

hunting drunk drivers, listen to a cat greeting me by name,

squint as a circus flea is harnessed to a tiny Ferris wheel,

interview shopping center Santas about what makes them cry,

watch the Super Bowl with boisterous inmates in a county jail,

attend an emotional graveside service for a murdered boy,

experience being a nobody at the elegant Academy Awards.

Stricken by poison oak tromping through a forest to waterfalls,

sunburnt on sensitive parts pitching horseshoes at a nudist camp,

where I feel like a windswept Apache without a loincloth.

A man strips to his swimsuit, revealing tattoos from ear to toe.

(Says he has more ink under his trunks, I take his word for it.)

Paid for sex, a middle-aged man tells me about a husband

who wept in his wheelchair watching him pleasure his wife.

Accompany a pilot scattering cremains over the ocean.

(Get dusted with bone and ash, experience an epiphany.)

At a county fair animal auction, a teen says goodbye to Aspen.

(She leaves with a check, her beloved lamb has a dinner date.)

Swear off sushi after the director of the county health lab

informs me diners can be infected by parasites, gag up worms.

Two female schoolteachers explain the changes enabling them

to lose a hundred pounds each. (Following up months later,

find them excavating large bags of barbecue potato chips.)

A mother worries her daughter will be the eleventh generation

in her family to be slowly blinded by retinitis pigmentosa.

A single parent lets a loving couple adopt her six-year-old son

because she’s afraid she’ll unleash pent-up violence on him.

For a week down and out in Santa Ana, eat and bunk in missions,

work day labor beside a guy bedeviled by psychopathic thoughts,

befriend Art, a white-haired hobo, ex-con who sleeps in the weeds.

(My series leads to a reunion of Art with a mother he fears dead.

Later, learn he wants freedom more than a roof, job, leisure suit.)

Present the truth, but sometimes not all the truth entrusted to me.

Should I trouble readers of my story about show dog breeders

by telling them of a young woman seeking comfort in canines

because of sexual abuse from a dad who ridiculed her naked body?

What about my article about a restless retiree who daily departs

his nursing home to ride buses along routes with familiar faces?

I choose an upbeat ending rather than his reply to my question

about why he keeps moving: “Because my son never visits me.”

You can’t avoid a sad closing when you write about the coroner

or a vet anxious to die so he can rejoin his buddies killed in battle.

But I prefer to leave my readers smiling so I volunteer to compete

against a little mutt in a log-rolling contest at Knott’s Berry Farm.

While a crowd watches, Penny spins me into the pond six times.

Afterwards, holding her shaking equally wet body in my arms,

I have an insight: Penny’s victory is no different than my defeat.

We’re all running on a log that will one day flick us off like a flea.

I walk away full of wisdom…and water. People stare.

A prophet often is not recognized or honored in his own hometown.