The Moment of Forgetting

You cannot remember

The moment of forgetting

But that is a moment

You’ll never forget

What did you forget

A key to your house or car

A pot cooking on the stove

Now you notice your forgetting

The moment when you notice

Your forgetting, you long for

Years of youth when you laughed at

Forgetting, delighted and innocently

Gone by the days of your ignorant past

The new knowledge is the opposite of

Wisdom growing. Forever you’ll remember

This never-forgettable moment

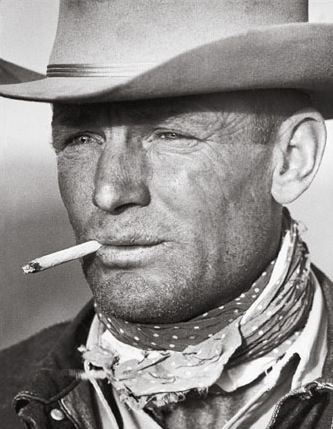

Author: The Beatnik Cowboy

Orman Day

The Kid

Palms without callous, shiny boots,

unstained jeans, arms without muscle,

a bologna sandwich bagged by Mom,

eighteen on the first day of my summer job back

when they called me the Kid.

Like my dad, his dad before him,

I labored for the Southern Pacific,

me on a gang out of L.A. erecting signals

that dinged, wagged, and blinked in '64

when they called me the Kid.

John and The Boss rode in the cab of the truck,

I sat in back with tools, a generator, a coil of wire,

Abie the Wop, Wally-Gator, an Indian named Chief.

War vets with stories to tell on freeway rides

when they called me the Kid.

Climbed wooden poles to hang wires.

swabbed signals with aluminum paint,

shoveled holes and trenches, scurried to the bin

for wrenches, wire cutters on sunburnt days

when they called me the Kid.

They laughed when they’d tease me,

“You ain’t never been in the saddle, have ya, Kid?”

And “You’re a chest man now, but when you’re our age,

Kid, you’re gonna be an ass man like us.” I always blushed

when they called me the Kid.

The Chief told me about riding home drunk from a bar,

turning sober at the sight of a grinning Devil.

Abie described life in the tenements, stickball and craps.

They knew I’d respond with wide-eyed attention

when they called me the Kid.

After carpooling home to a suburb,

I’d shower away grit and paint,

sit at my typewriter, listen to the Beach Boys,

carpenter the words of my first novel at a time

when they called me the Kid.

A confident swagger, sun-bleached hair,

money to pay for state college, buy Big Boys

and popcorn for freckled blind dates,

muscles to flex, dents in my naivete on the last day

when they called me the Kid.

If I worked on that crew now, they’d call me “Gramps,”

and I’d lean on my shovel, ruing the dust

that befell my novel about Abie, Wally and Chief,

heart-heavy remembering the hopes of that summer

when they called me the Kid.

Thomas M. McDade

Straight Arm

The IV is dripping

I can see each drop

but no soundtrack

I don’t last long

counting them

Keep your arm straight

or the fluid will cease

an alarm will go off

like a truck backing up

from here to Siberia

if the nurses and aides

are busy elsewhere

It’s freezing in here

Gridiron receivers

use the stiff wing

against defenders

Hell I raise my arm

a few times

as if curling a barbell

as if drunk

and challenging

the world to

arm wrestle, to try

to slam and crack

my knuckles

Help finally arrives

gently pushing flat

my illegal limb

she just says tsk tsk

Button pressed to

revive the stream

and mute the dumper

I check my blood

pressure on the monitor

121/86, a hoop score

Ma Yongbo

A Near-Forgotten Craft

Destruction is space, allowing new horrors to emerge

yellowed pages can no longer be turned

invisible ghosts make you cough incessantly

the painted landscape keeps shrinking

until real places become indistinguishable:

a century-old iron bridge as dark as a bagpipe

now creaks like a knee by the water’s edge.

Punish life by writing everything down

let the sunset hover forever in a still cave.

As long as this book is opened once

everyone will be resurrected, the precise machinery of hell

will start again, with wild winds, hail, and flames

with the asphalt stiffening their joints, the suffering of others continues

unbeknown to anyone.

Reliant on the reader’s sympathy and testimony

time continues like dashed lines in the snow.

Snow falls, falling forever,

yet never falling on the bent heads of pedestrians

always walking in the same place, never avoiding a snowfall.

Few believe in these kinds of games anymore.

Perhaps it’s just a harmless game

which offers us the image of time

like a watchmaker with weak eyesight in his workshop,

where metal parts and various-sized gears reflect the dusk light

through the carved glass revolving door, candlelight, flickers

at the door, an unidentified white horse appears

snorting with contempt, carrying the decay of generations.

Taryn Allan

The Opposite of Stars

The line of people turned the street into a catwalk

A Gothic walkway clinging to the venue’s wall

Velvet and leather buzzing within the dark

That was where we met, waiting for the doors

Seven-thirty entry, lights up at eight

Nine for the headline

We left before the first encore

Black-clad singularities spilling into the night

The opposite of stars

You were a statistic from the moment of our meeting

A possible end already coursing through your veins

An ambulance our taxi for the night

Namelessly you waited on a hospital floor

Sterile mockery of love; or lust, too early to tell

Apologizing to an omniscient nobody, pleading for your mother

The realization when questioned by a nurse

That I don’t know you at all

Your name as uncertain as the substance you’d taken

I stayed only a short while

Long enough to see them shoot you with Naloxone

A solution, perhaps. I did not wait to find out

I left you there, in that hospital

Walking away before my heart’s defences weakened

A blank angel of indifference

In uncertainty you’ve persisted

In memory, as in worry

An accuser of my own creation

There is a blank tombstone in my head

Capping a black hole

Where the off-switch to your memory should be

***

The Lost Harbour

The soft hour of the night

Reaching maturity

When the train station platform

Takes on a truer aspect

Dropping the mask of the day

Revealing the nothing underneath

A non-place for non-lives, victims and strays

The wordless music of the wind

A sleepless lullaby for all those gathered here

Some marooned by a last-train missed

Others by a lifetime of misses

Flotsam of the city one

Jetsam the other

The morning will decide

Who is to be salvaged

***

Orman Day

My Newspaper Days

Flog my dusty Super Beetle to the Register parking lot,

stay in my car to eat a ham sandwich, dry shave my stubble,

knot my grease-specked tie, flatten my flaring brown hair.

Grab the day’s first Diet Pepsi, stride into the newsroom

with its clusters of metal desks, cigarette and cigar puffers

exiled to a cloudy corner under the relentless wall clock,

lift my cold can to greet others who didn’t sleep in

after covering a meeting that dragged into the wee hours.

Sigh into a swivel chair in front of my typewriter if it’s ’80,

my computer if its ’83, read a note left by my editor,

sometimes clipped to a press release or a letter about a girl

selling her pictures to pay for her brother’s kidney transplant.

When you’re a general assignment reporter, you know

your words will get good play envied by those whose stories

about school boards and city councils are buried in back.

You better be clever, swift, empathetic, careful not to burn out

or make an embarrassing blunder requiring retraction.

Missed deadlines will get you demoted to a small-town beat

that forces you to keep a poker face while windbags

grouse about traffic flow, drainage ditches, trash pickup.

With a narrow reporter’s notebook tucked into my pocket,

sipping a fresh Diet Pepsi, bobbing my head to radio rock,

I maneuver on bald tires through Orange County, a region

of beaches, mountains, megachurches, oil rigs, Disneyland.

Cover a hillside brushfire, ride in a helicopter with a cop

hunting drunk drivers, listen to a cat greeting me by name,

squint as a circus flea is harnessed to a tiny Ferris wheel,

interview shopping center Santas about what makes them cry,

watch the Super Bowl with boisterous inmates in a county jail,

attend an emotional graveside service for a murdered boy,

experience being a nobody at the elegant Academy Awards.

Stricken by poison oak tromping through a forest to waterfalls,

sunburnt on sensitive parts pitching horseshoes at a nudist camp,

where I feel like a windswept Apache without a loincloth.

A man strips to his swimsuit, revealing tattoos from ear to toe.

(Says he has more ink under his trunks, I take his word for it.)

Paid for sex, a middle-aged man tells me about a husband

who wept in his wheelchair watching him pleasure his wife.

Accompany a pilot scattering cremains over the ocean.

(Get dusted with bone and ash, experience an epiphany.)

At a county fair animal auction, a teen says goodbye to Aspen.

(She leaves with a check, her beloved lamb has a dinner date.)

Swear off sushi after the director of the county health lab

informs me diners can be infected by parasites, gag up worms.

Two female schoolteachers explain the changes enabling them

to lose a hundred pounds each. (Following up months later,

find them excavating large bags of barbecue potato chips.)

A mother worries her daughter will be the eleventh generation

in her family to be slowly blinded by retinitis pigmentosa.

A single parent lets a loving couple adopt her six-year-old son

because she’s afraid she’ll unleash pent-up violence on him.

For a week down and out in Santa Ana, eat and bunk in missions,

work day labor beside a guy bedeviled by psychopathic thoughts,

befriend Art, a white-haired hobo, ex-con who sleeps in the weeds.

(My series leads to a reunion of Art with a mother he fears dead.

Later, learn he wants freedom more than a roof, job, leisure suit.)

Present the truth, but sometimes not all the truth entrusted to me.

Should I trouble readers of my story about show dog breeders

by telling them of a young woman seeking comfort in canines

because of sexual abuse from a dad who ridiculed her naked body?

What about my article about a restless retiree who daily departs

his nursing home to ride buses along routes with familiar faces?

I choose an upbeat ending rather than his reply to my question

about why he keeps moving: “Because my son never visits me.”

You can’t avoid a sad closing when you write about the coroner

or a vet anxious to die so he can rejoin his buddies killed in battle.

But I prefer to leave my readers smiling so I volunteer to compete

against a little mutt in a log-rolling contest at Knott’s Berry Farm.

While a crowd watches, Penny spins me into the pond six times.

Afterwards, holding her shaking equally wet body in my arms,

I have an insight: Penny’s victory is no different than my defeat.

We’re all running on a log that will one day flick us off like a flea.

I walk away full of wisdom…and water. People stare.

A prophet often is not recognized or honored in his own hometown.

Michael Lee Johnson

Trail of Tears in the Snow

Footprints in the snow, fresh.

Will your divorce lawyers talk

to Jesus this night—

set me chain-free.

Set you on your traveling ways.

Searching, we'll both be curiously searching.

Even hell has its standards burn with grace—

jukebox baby, we'll meet again

in the end, in that big black box.

Jesus suffers with the poor and the lost.

Jesus is the lead tempo rubato

4 both of us now bounce around

robbed of our stolen time.

Let me drive you home for the last time.

Coming home to go on separate paths.

Footprints fresh in the snow, 2 paths

forked off in different directions.

Hear diverse sounds —

on the FM radio, our favorite tune,

with age, it will become a classic

'Sympathy For the Devil,' The Stones,

jukebox, baby, put another quarter in.

Jeff Weddle

My Mother

My mother always bought grape jelly

and on special mornings

made scrambled eggs with pig brains,

which is better than it sounds.

She read to my sister and me every night

and that’s what got me through college,

because what she read was Shakespeare.

When I was maybe nine years old,

I broke a plate from her set of good China,

something irreplaceable,

and confessed in tears.

She kissed me and held me

and told me not to worry,

said the plate was just a thing

and it didn’t matter at all.

Sometimes she made vegetable soup

and I have never tasted anything better,

and I loved her salmon croquettes,

though she left in the vertebrae,

which was gross,

but gave us a little extra calcium.

She and my dad got in awful fights

now and again,

with their own tears and screaming

and great slamming of cabinet doors

but they stayed together until the end.

She had a heart attack

when she was almost fifty, a bad one,

but survived, and now, at 91,

remembers none of this.

My mother grew up poor,

poorer than anyone you ever knew,

but gave me riches.

I always buy strawberry preserves,

and they are delightful,

but maybe will try grape jelly

next time I go to the store.

There is so much that I have lost

with the years.

It’s been so long since I was home.

Not Zen

Maybe you see me

and wonder how I am serene.

This is the silence

of one absorbed into walls.

I wander between the hours

and feel nothing.

I look out the kitchen window.

I feed my dog a treat.

The world is full of music

but it is very poor music.

(Not bad, just poor.)

Maybe you see flowers

and believe they are beautiful.

Maybe you think of the bee.

I think of nothing.

This is absorbed into walls.

This is serene.

Maybe you see me

and decide I am old.

Maybe you see the cracks in my history.

Maybe you see me crashing into walls.

Poor music is everywhere,

but only old people

remember the disappointment

of warped records.

You don’t see me at all.

This is what I mean.

Peter Jastermsky

All the Things You Are

As uncertain as a question mark

As unbroken as a fledgling

As imaginary as a leapfrog

As buoyant as a second chance

As giddy as the last day of school

As creative as a conman

As mysterious as a silhouette

As complacent as an incumbent

As happy as a flat tire

As shady as a grifter

As resigned as a final draft

As certain as this handful of ashes

Alan Catlin

blue light special

the beautiful multi,

facially pierced

black girl wants

to know where to

get off the bus

for Aquarius Lounge-

plants her feet

on an Adidas

gym bag across

the way says, “I

got a long night

ahead of me &

I need some rest

how do you like

my hair? just

got it done today.

Matches my nails,

Midnight Blue,

that's my stage

name. Even my

piercing rings

shine under

the right lights.

Usually, I don't go

for none of that

New Age shit

but I hear tips

are good there

& that's all

that matters.

Hell I'd work

a K-Mart blue

light special if

the tips were

right